Black Heritage

Black Heritage Sunday

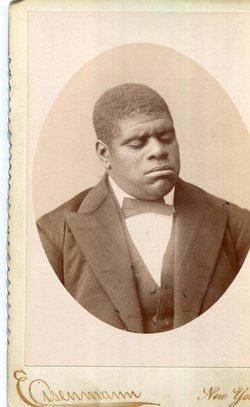

Thomas Greene Bethune --“Blind Tom”

1849-1908

Last Sunday Reverend Lester introduced us to a man named Will, who had no arms or legs but, in time, proved to be an excellent swimmer and ceased to let his disability prevent him from demonstrating his fine talent. Now meet Thomas Greene Bethune, popularly known as Blind Tom. His name has been given also as Blind Tom Wiggins and Thomas Wiggins Bethune. He, too, had a disability yet his talent far overshadowed the fact that he could not see. He was a composer as well as a pianist, who performed on plantations, before American and foreign dignitaries, toured in Europe, and appeared in major concert halls throughout his lifetime.

Born blind and a slave in 1849, near Columbus, Georgia, Tom was his parents’ twentieth child. Because he was blind, at first the plantation owner who purchased him thought that he could not perform as slave should and wanted to kill him because they thought he had no economic value. Soon, however, he was considered a bargain when purchased with his parents, because from infancy Blind Tom demonstrated an extraordinary fondness for musical sound and had exceptional memory. Some say that, by the age of two, he demonstrated that he was a musical genius. By age four he was a “musical marvel” on the Bethune plantation where he lived. He heard Bethune’s daughters play the piano, learned by ear, and gained access to the piano. By age five, he had composed his first tune, “The Rain Story” that came after heavy rain beat down on the tin roof of his home. Blind Tom was extremely attracted to sounds around him and repeated with accuracy the crow of a rooster or the sound of a singing bird. He would beat on pots and pans, drag chains across the floor, and do many things so that he could hear the sound. By age eight, he was hired out to a tobacco planter who promoted him in concerts throughout the United States. When the Civil War broke out, Blind Tom was returned to his owner who used his slave’s talents to benefit the Confederacy. His owners made several fortunes on Tom, earning as much as $100,000 from his European tour. Although frequently compared to a bear, baboon, or mastiff, and marketed as a “Barnum-style freak,” Blind Tom was undoubtedly the 19th century’s most highly paid pianist.

From age five onward, Blind Tom composed over 100 piano and vocal compositions. He included among his repertory works of Bach, Beethoven, Chopin and other European masters. His original compositions included parlor waltzes and marches. He had remarkable vocal ability and wrote poetry as well. Blind Tom remembered various lectures and could recite poetry or prose in several languages, reproduce sounds of nature, machinery, and various musical instruments—all demonstrating his remarkable ability to remember. He has been referred to as a “human parrot.” Eventually, he learned 7,000 pieces of music, including hymns, popular songs, waltzes, and classical works.

Blind Tom referred to himself in the third person; for example, both on- and off stage he said, “Tom is pleased to meet you,” not “I am pleased to meet you.” He could give renditions of three tunes simultaneously in several keys and play the piano equally well whether sitting or standing.

In 1860, Blind Tom performed before President James Buchanan in the White House, the first African-American to give a command performance there. Although none of his original recordings are known to exist, some of his sheet music is available. In 1976 the people of Columbus, Georgia, erected a commemorative headstone for him. He was the subject of a play called “Hush.” In 1981, he was the subject of a film, Blind Tom, The Story of Thomas Bethune; other films have been based on his life and work. A music educator wrote her doctoral dissertation on him; it was published in 1902 as a book titled Blind Tom: The Story of Thomas Bethune. Since then, other books and articles have been written about him, including a sequence of poems published in 2016. In 1999, some of his original compositions were recorded on CD. The well-known singer Elton John included in his 2013 album The Diving Board a piece about him titled “The Ballad of Blind Tom.”

What a life for a blind slave whose genius caused audiences to praise his extraordinary talent and disregard his disability! If he had eyesight, could it have made a difference? Would he have developed the ability to memorize speeches, sounds from nature, all sorts of noises, and thousands of musical pieces. And what about his compositions? We could spend considerable time praising one who drew so heavily upon his genius that is it safe to say that he was not disable. He was, instead, an enabler—one who, from childhood and through his work, encouraged others to appreciate music and the spoken word. Blind Tom or Thomas Greene Bethune, or Thomas Wiggins Bethune, or by whatever name he is remembered, suffered a major stroke in April 1908 and died the next June at age 59, as a free genius. He was buried in the Cemetery of the Evergreens in Brooklyn, New York—near the place where he lived with his final owner until he was free.

Researched and submitted by Dr. Jesse Smith